UMBRA EX MACHINA

We carry our past with us, to wit, the primitive and inferior man with his desires and emotions, and it is only with an enormous effort that we can detach ourselves from this burden. If it comes to a neurosis, we invariably have to deal with a considerably intensified shadow. And if such a person wants to be cured it is necessary to find a way in which his conscious personality and his shadow can live together.

“Answer to Job” (1952). In Collected Works of Carl Jung, 11: Psychology and Religion: West and East. P.1.

The lessons from the Book of Job have long been theological touchstones for me, just as Jung has been my go-to therapist in times of crisis, so this quote from Jung, in the context of his Answer to Job, is fitting for this post.

With Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence (ML/AI) in the ascendency and clever new applications of existing models and new model architectures emerging at at increasingly innovative pace, we are discovering more and more can be done with less and less. Bucky would be proud. But I think Jung’s advice must also be considered at this juncture.

The Human Shadow

We all have a shadow — that subconscious dark part of us that we deny at our own peril. “Our issues are in our tissues,” or so the saying goes. To avoid the painful process of recognizing and processing our own shadow — those exiled and repressed parts of ourselves often born of trauma — is to remain unmindful of our own reactive and self-destructive behaviors. I will assert that if you have not mindfully engaged a process of fully understanding and accepting your own shadow, you may be suffering needlessly.

Shadow work can be very beneficial. But that’s not the point of this blog. This blog is about the collective shadow.

The Collective Shadow

Jung pioneered the idea of the Collective Unconscious. Per Jung, there is a layer of the unconscious mind in every human being that we are born with. Imagine a database in the cloud with blob storage — objects representing classes — bundles of functions that might be instantiated based on operational triggers. Archetypes are such patterns. Such objects might lie dormant in our unconscious mind until a trigger event occurs, thus instantiating said objects into subconscious apparatus. Our behaviors and thoughts are then shaped to a great extent by the new functions. While stretching the analogy to make the point, I believe the point is well made: Some fundamental behavioral stuff is baked-in.

Just as each of us harbors psychological shadows, many have argued that a collective shadow colors group or even national actions and reactions. My own admiration of the ideas of Jung is tempered by the realization that his own book of shadows probably impacted his world views insofar as his views on the character and politics of the German people in the prelude days of World War II were concerned. But in my view, Jung’s observations and the archetypal channeling of group fear and rage is exactly the point.

Well Adapted for War

If we accept the fact that human beings evolved culturally from early proto-sapiens, and that the oft mischaracterized ‘survival of the fittest‘ goad had something to do with that evolutionary path, then it follows that we are well adapted to war. If, on the other had, we accept a more Biblical view, it still follows that we are well adapted for war. The Old Testament is filled with tales of conquest with a clear tribal manifest destiny as the driving force.

What does it mean to be well adapted for war? It seems to me that the essential trait we must posses is the innate ability to easily dehumanize the enemy. In order to literally slit their throats, rape their women and enslave their children we must have the capacity to view the enemy as non-human monsters. Natural selection would have long ago weeded out any tribe that held empathy for the other team.

So let us stipulate, 1) yes there is a collective unconscious that can and will color group or national activities, and 2) all too often the shadow aspects of that collective can lead to unspeakable horrors and normalization of inhumane treatment of our fellow man during ‘us versus them‘ conflicts. Is that okay? Are we all okay with unconscious flailing and conquests based on demonizing the other?

Taming the Collective Umbra

For individuals embarking on the painful journey of shadow work, first one must decide to look for their shadow and then start the process of spotting it. This is not an easy path. But there is no greater pain than the pain you get from trying to avoid the pain. Regardless of the pain involved, to emerge from addiction or depression or a litany of bad life choices, shadow work might be the only path that will lead to a true healing, and is therefore the least painful choice in the long run. The same is true for the collective shadow. Everything else, whether it be medication, meditation, or manipulation, only postpones the inevitable in a collective fog of denial.

It is not an easy thing to face ones shadow. But many individuals do so, and do so successfully. I believe we are now developing the tools to help each of us face the collective shadow in order to effectively do that work. Alas, the denial is strong in us.

Is prejudice based on identity real? Of course! Many individuals are ugly with prejudice. Are we collectively bigots? Yes. I may not be. In fact, I insist that I am not. You may not be. You may also insist that your are not. But collectively, yes, we are. Why? Is identity prejudice a manifestation of the evolutionary selection criteria that gave rise to the here and now? Is there a bigot archetype that gets instantiated when ‘us versus them’ triggers get pulled? Is prejudice shrouded in the class of ‘otherness’ much like national identity? How can we measure collective bigotry? And if we can measure that collective set of traits, and if we consider shadow work to be a painful yet healing path, then are we not better off collectively recognizing and embracing that shadow part of us for what it is? Truth be told, Jung himself can be viewed as a bigot by the standards of today.

We have the means today to start to peer into the abyss of the collective unconscious. Those means have been emerging as advances in Natural Language Processing (NLP) unfold. Massive, expensive projects have given rise to remarkable Language Models (LMs). GPT-3 is but one example. To the chagrin of many observers, although language models like GPT-3 can write poetry, they often amplify negative stereotypes, which we universally agree is unacceptable. Despite the fact that our LMs might be trained using actual views, opinions, statements and thoughts expressed by our fellow human beings, when the results drift too far from some socially acceptable range of beliefs, we cannot accept the outcome. If my shadow is always with me, part of me, and the collective shadow part of us, am I not dehumanizing myself when I deny my shadow?

Rather than take steps to scrub those undesirable characteristics from the AI, might we also make good use of those unruly models that might more truthfully reflect those unconscious collective shadows that stalk us?

When we make war, we always go to war against enemies we have dehumanized, whether it be today’s proxy battles, or political battles, or cultural battles. We are good at dehumanizing other.

Thank you God and Darwin, for without that very useful dehumanizing skill, wars would be much less pervasive and far less profitable. </sarcasm>

Instead of silencing collective shadow voices discovered in language models, what if we embraced them as tools of growth? History is filled with the stories of societies that forced their shadow on others. All wars can be viewed as such. All conflicts arise from projecting collective shadows on the other.

It is a dark page in human history when people make others bear their shadow for them. Men lay their shadow upon women, whites upon blacks. Catholics upon Protestants, capitalists upon communists. Muslims upon Hindus. Neighborhoods will make one family the scapegoat and these people will bear the shadow for the entire group. Indeed, every group unconsciously designates one of its members as the black sheep and makes him or her carry the darkness for the community. This has been so from the beginning of culture. Each year, the Aztecs chose a youth and a maiden to carry the shadow and them ritually sacrificed them. The term bogey man has an interesting origin: in old India each community chose a man to be their ‘bogey.’ He was to be slaughtered at the end of the year and to take the evil deeds of the community with him. The people were so grateful for this service that until his death the bogey was not required to do any work and could have anything he wanted. He was treated as a representative of the next world.

I claim we are missing a critically important opportunity when we dismiss our more objectionable language models out of hand. Of course we must be mindful of use case. Most certainly we want unbiased, moral, ethical language models that reflect our better angels regardless of our own shortcomings. Reflecting the best of all that we might aspire to be as human beings, we want those ethical attributes to be embedded in the LMs that drive our applications. Why? That is a fine question for my upcoming blog post.

But if true societal healing rather than denial, deceit, and political manipulation is important (and I for one claim it is more important now than ever), then we should embrace those coarse, bigoted, prejudiced language models and preserve their disgusting and offensive character flaws. We must do so in order to mindfully face those shadows and understand they are currently baked-in to the substance of our humanity. Those misbehaving LMs are not to be rejected but rather lauded, understood, and used as mirrors, for those are windows into the nether realms of our collective unconscious mind. Our Umbra Ex Machina.

Which is better: to wage all-out war against the enemy we have so easily dehumanized, or grow to understand the forces that drive us to violence as we fail to recognize the humanity of the other? What are these rebellious LMs trying to tell us that we would so ardently silence and pretend does not permeate our collective character?

It has always been us versus them. But in this particular chapter of the Network Age we now have mirrors for the collective us and them that we have never had before. Wonderful digital mirrors which we can choose to use to improve our collective well being, or ignore what we hate in ourselves at our own peril. We now have collective unconscious doppelgängers in silico. We have a glimpse into the collective shadow that haunts us.

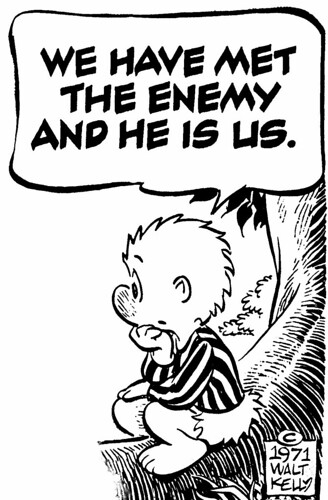

We have met the enemy, and they are us. Let’s not lose that battle.

All of this presumes a shared ethical framework — an a priori moral structure upon which we fashion civilization itself. What do our machines have to say about that? Stay tuned.

Leave a Reply