Let Us Reason Together – part 2

“‘Come now, and let us reason together,’

Says the Lord,

‘Though your sins are like scarlet,

They shall be as white as snow;

Though they are red like crimson,

They shall be as wool’” (Isaiah 1:18)

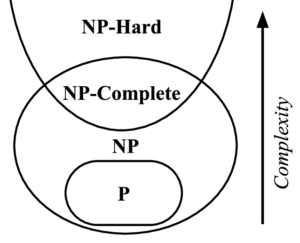

In part one of this series I made the assertion that NLP is hard. We might even say it is NP-hard, which is to say that in theory, any model we would hope to engineer to actually ‘solve’ the context-bound language of human beings is at least as hard a mountain to climb as is the halting problem for any given (sufficiently complex) program.  For an analysis for linguistics from the perspective of machine learning, Ajay Patel has a fine article exploring the matter.

For an analysis for linguistics from the perspective of machine learning, Ajay Patel has a fine article exploring the matter.

Although we have witnessed incredible advances in machine intelligence since Turing first asked, “Can Machines Think?“, we are still pondering exactly what it means to ‘think’ as a human being. The field of consciousness studies has produced laudable theories, to be sure. But we don’t yet know — we do not yet agree on — what precisely we mean by ‘consciousness,’ let alone share a congruent theory as to what it is. From pure (eliminativism) denial to panpsychist projection to good old school dualism, we still wrestle with the mysteries entangled in the most common aspect of human existence. We know it when we experience it. But we cannot say what it is. It’s no wonder Turing ultimately threw up his hands when he realized that any existential foundation beyond solipsism required an acceptance of other as conscious. Thus, if it walks like a duck, and quacks like a duck….you know the rest.

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis asserts that the structure of language shapes cognition; my perception is relative to my spoken (thinking?) language. Some linguistic proponents of this view hold that language determines (and necessarily limits) cognition, whereas most experts only allow for at least the influence of mother tongue on thought. Wittgenstein poured the foundation and Sapir-Whorf laid the rails. And apologists for cultural relativism were empowered in the process.

But do I really think in English?

Have you ever known what you wanted to say but could not remember the precise word? You knew that you knew the word you wanted to say, but you could not find the specific word in your cognitive cache. Some internal mental subroutine had to be unleashed to search your memory archives; within moments the word was retrieved. But you knew you wanted to say something — some concept or idea — but the associated word did not immediately come to mind.

In 1994 Steven Pinker published The Language Instinct, in which he argues that human beings have an innate capacity for language. Like Chomsky, evidence of a universal grammar is presented. Per this view, human beings instinctually communicate, honed by evolutionary forces to succeed as hunter-gatherers. Written language is an invention. Spoken words too are inventions, to facilitate the natural instinct for structured communication. Like a spider’s instinct to weave a wab, human beings have an instinct for structured communication. If this is so, then we ought to be able to discern the rules of the universal grammar, and eventually automate the production of words such as to effectively and meaningfully facilitate communication between humans and machines. And yet, some six decades since the dawn of computational linguistics, we are still frustrated with conversational agents (chat bots). We do not yet have a machine that can pass the Turing Test, despite many attempts. And NLP is still confined to a short list of beneficial use cases.

Must we solve the hard problem of consciousness in tandem with finding the machine with communication skills that are indistinguishable from humans? Per Turing, it’s the same problem.

Neuro-symbolic Speculation

Despite impressive results from modern deep learning approaches in NLP, Turing’s challenge stands: invictus maneo. So if neural networks aren’t enough, then what? We’ve tried rules-based systems. That didn’t work. Despite a resurgence of knowledge graphs, are they not too subject to the intrinsic problems expert systems faced in the 1980s?

Enter Gary Marcus. The solution, per Marcus, is a combination of deep learning and knowledge (rules-based) AI. It’s the next thing. The revolution is here and we have a flag….maybe.

To be fair, Marcus did not invent the idea of Neuro-symbolic AI. In all probability it was IBM. In my view we never give enough credit to IBM for leading the field of machine learningin so many ways. Maybe because they’ve been around since the dawn of the 20th century and their stock pays a decent dividend. But Marcus has planted the flag of Neuro-symbolic AI firmly in the modern noosphere, and so we speculate with him here.

His basic idea is simple: take two complementary approaches to AI and combine them, with the belief the the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. When it comes to solving the hard problem of language, which appears to be directly related to consciousness (and therefore AGI) itself, we must stop hoping for magic and settle for more robust solutions for NLP-specific use cases. Our systems should being with basic attributes: reliable and explainable. That seems like a logical step forward. And maybe it is.

Marcus has suggested a 4-step approach to achieving this more robust AI:

1. Initial development of hybrid neuro-symbolic architectures (deep learning married with knowledge databases)

2. Construction of rich, partly-innate cognitive frameworks and large-scale knowledge databases

3. Further development of tools for abstract reasoning over such frameworks

4. Sophisticated mechanisms for the representation and induction of cognitive models

Sounds reasonable, doesn’t it? And perhaps the Marcus recipe will incrementally improve NLP over the next decade to the point where chat bots at least become less annoying and model review committees at Global 2000 firms will have ethical ground cover when it comes to justifying and rationalizing predictive results, regardless of how unsavory or politically incorrect they may be.

But Turing Test worthy? Maybe not.

In part 3 we will dive a bit deeper; it will be rewarding.

Leave a Reply